For this month’s book review, we’re diving into How To Learn the Alexander Technique, by Barbara and William Conable. One of my students started with me in the midst of reading this book, and lent me his copy to read while we worked together. I enjoyed it enough that I’ve since bought my own copy to use for this review.

For this month’s book review, we’re diving into How To Learn the Alexander Technique, by Barbara and William Conable. One of my students started with me in the midst of reading this book, and lent me his copy to read while we worked together. I enjoyed it enough that I’ve since bought my own copy to use for this review.

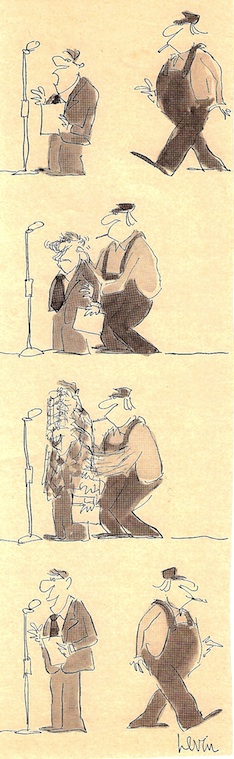

How To Learn… takes the form of a manual for students of the Alexander Technique. Alexander’s work is presented in a workbook style, with space to write in your own observations and periodic prompts to write or sketch as a way of deepening your understanding on a concept. The specific focus of this manual is on connecting the Alexander Technique to the technique of Body Mapping that William Conable developed during his work with musicians at Ohio State University. The book is written informally in first person, giving a conversational feel to the discussions presented. Just as a side note: while the cover says it is by both Barbara and William Conable, both the preface and the text’s use of ‘I’ rather than ‘we’ give the impression that Barbara is the main author, so I will be referring to her in the singular here, for simplicity’s sake.

The discussion of Body Mapping is one of the many strengths of this manual – it’s a powerful tool to add to one’s experience with AT. The workbook style provides copious illustrations and anatomical drawings to aid understanding, and allows for plenty of written and sketched explorations of the concepts discussed. Conable has some great insights into Alexander’s work, and some great ways of phrasing ideas that really resonated with me. While the writing does come off as a bit biased towards AT at times, one could argue that that’s to be expected from a book written by teachers of the work. The book is intended to be used by students who are already taking lessons from a teacher, as a supplement to their work in their lessons. Conable stresses the idea of re-reading and ‘playing’ in this book as the student learns, returning to concepts as their understanding develops. “My students who really live with the book…seem secure in their learning.” (p. xi) She mentions that it would also be useful for music students who have AT-literate teachers, or for AT teachers themselves.

How To Learn… focuses on an introduction to the Alexander Technique and its connection to the idea of body mapping – essentially a technique for visualizing your own sense of your physical self and what inaccuracies may be present within that mental map. The manual begins with an overview of the Technique itself, continues through a discussion of the kinesthetic sense, and from there into body mapping. It then connects body mapping to all kinds of other applications and uses for the Technique, from things like exercise and sleep to stage-fright and survivors of abuse. It makes liberal use of standard anatomical drawings as well as more free-form examples of body maps and other visual representations of the concepts discussed. The manual also gives examples of common body mapping errors – with large warnings in the margins stating “COMMON ERRORS,” presumably so that if you’re flipping through the book you won’t hit upon one of those pages and mistakenly assume the statements made on it are truthful.

I was pleasantly surprised to see that How To Learn… discusses several aspects of the Alexander Technique that tend to get glossed over or forgotten in other works. These include things like why we pull down, the rotational aspect of the phrase ‘Forward and Up,’ and a discussion of energy. Conable also has a wonderful way with language; my notes are full of direct quotes, and she often gave me terms for things I do naturally in a lesson – like body mapping, in fact! She spends ample time highlighting the beautiful contradictions of AT – the self is full of paradoxes, and I appreciate that she names them and gives permission for two disparate things to exist simultaneously in one self. The discussion of body mapping also makes for some really unique insights, like the distinction between a muscle map and a skeletal map. I greatly appreciated the acknowledgement that our body maps need not be internally consistent – different activities can dictate different types of maps to come into play. We can think of the bones to enhance the sense of support, or the spaces between them to emphasize freedom, and which version we choose can change depending on what is needed most at that moment.

I had to reach pretty far to find weaknesses in How To Learn…, but I suppose her discussion of somatics does come off as a bit biased in spots. At one point she describes AT’s relationship to other somatic practices as “one of the really important ones” – comparing it to a corner piece of the body puzzle, a practice that helps to orient all the others. While I might personally agree with her, it does show a bit of bias. We could expect as much from an AT teacher, though – we’ve chosen to dedicate our lives to the practice; we have reason to be a little biased! It doesn’t affect my enjoyment of the manual or its usefulness as a whole, and given that its intended audience is current students you can forgive Conable for preaching to the choir a bit. What is less forgivable is the rather truncated overview of Alexander’s core principles. Conable talks about downward pull and primary control, but then transitions almost immediately into her Laws of Human Movement, her own work based on Alexander’s ideas. She articulates two of Alexander’s principles – other authors I’ve reviewed on this blog have discussed up to seven! She does acknowledge the importance of reading F. M.’s books to hear the work in his own words, though, so that tempers my disappointment a bit.

Overall, How To Learn… is a good introduction to the Technique, but probably more useful after a student has had a few lessons. It would be useful to pretty much all students, but there is a definite focus on physicality, so those students who tend towards a physical worldview (dancers, athletes, etc.) might benefit more strongly. Then again, those unused to physicality might find they have more grievously-inaccurate body maps, and thus see dramatic results from correcting those maps. In general, I would recommend this manual to my own students as a supplement to our lessons, and I think anyone currently in lessons would benefit from working through it as well.

The Nitty-Gritty

Title: How To Learn the Alexander Technique: A Manual For Students

Author: Barbara Conable & William Conable

(c) 1991 by Barbara H. Conable and William Conable

ISBN: 0-9622595-4-3

Status: available on Amazon

Aliases: none

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Concept Spotlight: Baby Feet

If you’ve had a lesson with me, you’ve probably had a table turn, and if you’ve had a table turn, you may have experienced a particular leg-moving technique that my teachers called ‘baby feet.’ This technique involves rotating the knee outward and sliding the foot along the table to extend the leg, as opposed to the simpler version that extends the leg up in the air before lowering it to the table. But why is it called ‘baby feet’? Well, let’s let Baby Stafford show you:

Baby Feet from Ellen Deutsch on Vimeo.

Most babies do some version of this, hence the name. It’s another of the ways the Murrays have incorporated developmental movement ideas into their work with the Technique, and I’ve found it’s a great way to free up tight hips and release lower back muscles. But why do babies do this in the first place? They don’t have tight hips, do they?

Well no, they don’t, but it’s actually for a fascinating reason. Ever wondered why it seems like babies are made of rubber? It’s because a lot of things about them are not really fully formed until well after birth. Most people know about the plates in a baby’s skull that fuse much later in life – that’s why the ‘soft spot’ is so important to be careful around – but not many people know about the curious state of a newborn’s hips. Namely, a newborn doesn’t have them!

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint; the head of the femur slots into a socket on the pelvis to allow for freedom of movement in all directions. However, the construction of the hip joints means that the pelvis is one of the widest parts of the body, and when it comes to being born, wider is definitely NOT better. Part of the reason for the separate plates in the skull is so that it can mold to squish its way out of the mother, and in general, it behooves a newborn to be able to become as narrow as possible to facilitate birth. To that end, a newborn baby’s pelvis doesn’t yet have sockets for the heads of her femurs to lock into; they’re simply flat planes with the heads of the femurs resting up against them. This way the legs can dangle lower down and narrow her frame for birth. (Incidentally, this is why carriers for newborns need to have support for their hips; if the crotch-piece isn’t wide enough the legs will dangle and cause problems in their development.)

While this is preferable for the actual birthing process, a lack of hip joints is a pretty big obstacle in the way of being able to put weight on her legs! So, a baby has to create her own hip joints before she can support herself with them. This ‘baby feet’ movement pattern is the baby’s way of literally grinding out their own hip joints! The baby explores all the different movement possibilities for their hip joints with these movements, and creates the shape of their sockets to match the balls on their femurs. If you’ve ever wondered why it’s possible for someone to have asymmetrical hip joints, this is why – they have to make them from scratch in infancy!

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Quote of the Month: September 2017

“Evolution happens as each generation of living things interacts with its environment and reproduces. Lamarck got at least that part of it right. Those natural designs that survive to reproduce pass on their genes. Those that don’t successfully reproduce disappear; their genes disappear as well. It’s survival of the hang-in-there’s, or the made-the-cuts, or the just good-enoughs.”

Excerpt From Undeniable: Evolution and the Science of Creation, by Bill Nye & Corey S. Powell.

After a long break, we’re back! I apologize for dropping off the grid for so long; I was in the process of adding another miniature Stafford to the world! But now as I return from my maternity leave and begin incorporating students back into my new schedule, I’ve been thinking a lot about this quote from Bill Nye’s amazing book about evolution. My life for the first five or six weeks of my daughter’s life was hectic and sleepless, and my own use began to suffer for it. She’d only breastfeed in very specific positions that were hell on my back and shoulders, and even now she wriggles so much that it’s hard to stay released when she might fling herself out of my arms at any moment.

As I begin September and start the process of returning to work, I’ve prioritized taking some time each day to work on my own use and reconnect with Alexander’s teachings. This quote from Bill Nye has been resonating with me, specifically in the idea of ‘the hang-in-there’s, or the made-the-cuts, or the just good-enoughs.” I connect this idea to Alexander’s concept of means-whereby and end-gaining, because for me, I’ve been end-gaining about wanting to be perfect right away. My mind has been struggling with the thought that if only I could just let go, think forward and up and stay free, everything would be great. And I’ll inhibit and direct and be good for a few minutes, until the baby cries or crashes her head into my jaw and then I’m back to tensing up to protect her.

The quote above comes from the end of a chapter in which Bill Nye talks about the incremental change of evolution, and the fact that at every step along the way, the whole organism still needs to be functional. He gives the analogy of trying to change a two-wheeled push cart (you know, the kind that you sometimes see old ladies bring to the grocery store) into a bicycle, but in tiny increments, and at each step of the process the whole thing still has to function well enough as a push cart, or you’ll leave it by the side of the road and it’ll never get to be a bicycle. I’m comparing that to my experience as a new mom, where I’m trying to reincorporate my good Alexander use, but I still have to be a mom at every step. Baby still needs me to feed her every few hours, and I still have to carry her in particular ways or she’ll get upset. But I can figure out incremental ways to do those things while also maintaining my use. I don’t have to get it exactly right immediately; just keeping the process going is helping me in the long run.

So for this month, I’m channeling the bottom-up organization and incremental change of evolution and settling for being ‘just good-enough.’ If I can spare a few minutes for some constructive rest while she naps, or think about my use while pushing the stroller up our big hill, then that’s that for today and I’ve done what I can. Inhibit, direct, and hang in there.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Last week we discussed the vestibular apparatus, and how the structures of the inner ear help us to sense the motion of the head in relationship to the rest of the body and to gravity. Today we’re going to look at a highly-specialized use of the vestibular apparatus, in the form of the dance technique known as ‘spotting.’

For starters, take a look at ballet virtuoso Gillian Murphy doing a classical ballet trick known as “32 fouettes.”

The 32 fouettes are a staple in almost every classical ballet. The reason, at least according to legend, is that the ballerina who invented the technique of ‘spotting’ was the principal dancer in one of the largest ballet companies at the time. She was the only person able to complete these turns without getting dizzy and falling over, and the resident choreographer of her company (who is responsible for most of the classical ballet repertoire of today) was so impressed with her ability to turn without dizziness that he put the fouettes into every one of his ballets, just to let her show them off. And of course, that means every ballerina of today has to learn this once-impossible trick!

‘Spotting’ as a technique involves fixing the gaze on a specific object for as long as possible, leaving the head stationary while the body rotates below it. When flexibility of the neck does not allow for any more rotation, the head is quickly snapped around to the other side of the body and the eyes find the same object in advance of the body rejoining the head at the end. Watch the video again, and pay attention to Murphy’s head in relation to her body. You’ll see her head spends much of its time facing the audience with brief jerks of quick movement, while her body moves at a consistent speed.

The reason spotting works is because of the nature of the vestibular apparatus. By holding the head relatively still as long as possible, the dancer minimizes the sloshing of the fluid in the vestibular structures. Minimal slosh equates to minimal sensation of movement, which translates to minimal perception of being off-balance (more so if the dancer is successful at remaining poised over her supporting leg so that there is little to no lateral shift as well).

But that might not be all. A study from 2013 published in the journal Cerebral Cortex suggests that in addition to decreasing the sensory feedback from the vestibular apparatus, dancers may actually be training their brains to selectively ignore that feedback, causing their vestibular sense to effectively shut off in very specific ways. When spun around in a chair in a dark room and then asked to wind a handle in time with how quickly they felt they were still spinning after they were stopped, the dancers’ eye reflexes and perceptions of spinning stopped more quickly than those of non-dancers. The study also found, through brain scans, that the area of the cerebellum responsible for processing vestibular sensory input was smaller in dancers than in non-dancers.

The AT teacher in me sees this as a fascinating example of the mind/body connection, in a reversed relationship than we usually think about. This is the body influencing the mind on an anatomical scale. The dancer in me finds it fascinating that we have trained ourselves to ignore our vestibular sense in very particular ways, and is curious to look for other contexts in which we ignore our vestibular sense.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

In last week’s Quote of the Month, we talked about our unnamed sixth sense, the kinesthetic sense. This is the sense that gives you information about your self and your relationship to the space around you. Have you ever stopped to wonder how it is that you can instantly know your relationship to gravity, even with your eyes closed and your body suspended? “How You Stand, How You Move…” by Missy Vineyard answers this question by explaining the mechanics of your vestibular sense. She suggests that this be considered the seventh sense, unique and distinct from the movement sense, though it can just as easily be considered part of the same sense of yourself relative to external space.

The vestibular apparatus is comprised of several tiny, fluid-filled tubes in the head whose inside walls are covered with tiny hairlike receptors. As you move, the fluid pushes on the receptors in various parts of the tubes, and the information is sent to the brain and interpreted as movement of the head in space. The apparatus also includes two small basins of fluid, each of which has particles of calcium within the fluid. Moving your head jostles these basins (like shaking a snow-globe) and causes the calcium particles to slowly fall through the fluid towards gravity. They land on the inner walls of the basin, where sensory receptors pick up the location of the particles and send that info to the brain, which interprets it as the location of gravity relative to the head. This apparatus seems at once elegant and simple – how do you tell what direction gravity is? Drop something!

This, incidentally, is why dancers learn the technique of ‘spotting’ – when doing multiple turns, a dancer attempts to keep her head still for as long as possible before whipping around to focus on the same spot as quickly as she can. This keeps the fluid within the vestibular apparatus from sloshing too much, and allows her to train her senses to compensate for the remaining slosh and prevent her from getting dizzy. After all, while the snow-globe is shaking the snow within it doesn’t know which way is up; it’s only once the fluid settles that it finds the direction of fall. We’ll talk more about spotting next week in our Everyday Poise.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Quote of the Month: September 2016

“The fact is there are six senses, and we name five. In addition to sight and hearing and touch and taste and smelling we have a movement sense, known more technically as the kinesthetic sense. The kinesthetic sense tells you about your body: its position and its size and whether it’s moving and, if so, where and how. That is the information that corresponds to color, depth, and shape in vision or salt, sweet, and bitter in the gustatory sense.”

~Barbara and William Conable, “How to Learn the Alexander Technique: A Manual For Students”

I’m reading this book at the recommendation of one of my current students, and loving its no-nonsense straightforward tone and valuable insights. This paragraph resonated with me strongly, specifically, the idea that for some reason, we fail to name one of the major senses when going through them with our young children. We talk about touch, taste, smell, hearing, sight…but where is the internal sense? Where is the sense that allows us to close our eyes and accurately touch a fingertip to the end of our nose? Where is the sense that allows us to identify whether our body is upright or horizontal? Where is the discussion of our kinesthetic sense?

I was at the dentist yesterday for some work, and I took the opportunity while getting numb from the novocain to explore this sense myself. I found that I could run my tongue over the tooth in question, and while my tongue did feel the presence of the tooth, it felt like a foreign object rather than a part of me. The nerve endings in the tooth itself had been numbed, so my tooth’s kinesthetic sense was shut off. The tooth felt to my tongue like a wall of bone, and I received no sensation back from the tooth at all about what the tongue felt like. This was a clear example of my own kinesthetic sense, and just how involved and fine-tuned our ‘unnamed’ sense is.

One of the biggest hurdles in learning the Alexander Technique is getting used to listening to our kinesthetic sense, a sense that for most of us goes largely unnoticed in our daily lives. The Conables state, “Your mother and father, as representatives of the culture at large, named seeing and hearing for you. They taught you directly the difference between blue and green and loud and soft. They probably did not, on the other hand, name kinesthesia for you, nor did they directly teach you basic kinesthetic distinctions like tense and free or balanced and unbalanced.” (P. 19) Why is that? Why do we not teach our children about their sixth sense? And what observations could our children teach us if they were made consciously aware of their kinesthetic sense from a young age?

So for the month of September, let’s introduce ourselves to our kinesthetic sense. How much can you sense about yourself – the way you move, the level of freedom or tension in your joints, the relative placement of your limbs and torso? As you read this right now, where are your elbows in relation to your ribs? Are you clenching your jaw? What direction is gravity relative to you? Let’s explore!

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Everyday Poise: Anatomy of a High Jumper

In honor of the Rio Olympics, I decided that today’s Everyday Poise should return to the world of Olympic athletes. My very first Everyday Poise article was about Shawn Johnson and her balance beam skills, so today, let’s leave gymnastics and check out some track and field. Specifically, let’s look at the High Jump.

The official Olympic YouTube channel has a lovely short piece interviewing medalist Derek Drouin about the ideal build for a high jumper. Watch the video below, and then we’ll discuss.

So, as you can see from the video, there’s a lot going on in the mechanics of a high jump. Derek mentions that most of the work is done on the ground, during the approach and take-off. He mentions that the approach is not a straight line; it’s a bit of a curve leading into it. That is really telling for me; essentially, what the high jumper is doing is setting up a spiral. Using our Developmental Movement principles, let’s look at one of the slow-mo replays again. The approach is a curve that begins a spiral to one side, and the take-off uses the outside hand and leg to twist to the other spiral as the athlete goes over the bar. Given that, the initial approach is kind of like coiling a spring; releasing the tension from the wind-up allows more of that momentum to be transferred to the height of the jump itself.

As far as the actual jump goes, you’ll notice that the jump takes the athlete over the bar face-up; they are going into a secondary curve (arching the back) to allow them to clear higher distances. Watch the face and eyes of each successful jumper; there’s a sharp intention behind the eyes as they go into the take off, and they let their head lead the ensuing spiral and secondary curve. Most of them do this by looking ahead of them, reaching with their eyes to see the space behind the bar as they go over. This keys in to the Developmental Movement idea that the head leads and the body follows, and can be connected to the intention behind the eyes of a toddler as they crawl across the floor – just as the baby’s desire to get somewhere coordinates her whole self’s activity, so the high jumper’s desire to see the space behind the bar takes him into that arched secondary curve that allows him to clear higher distances.

And on that note, if you watch the clips near the end of the video where he talks about bar awareness and it shows athletes failing to clear the bar, check out their head and eye positions as they miss their targets. Most of them start out great, but something stops them from continuing their curve and spiral. Whether it’s feeling themselves grazing the bar and getting disheartened or simply getting psyched out, something causes their eyeline to stop moving, which cuts off the spiral and the curve and lowers their hips enough to knock the bar down – and it’s almost always the hips that hit the bar first in these cases. These athletes’ torsos are horizontal on the way down to the mat, rather than the successful athletes’ head down, nearly vertical in some cases, as the spiral completes with their feet clearing the bar. In fact, some of the successful examples from earlier in the video wind up ending their jump with a shoulder roll on the mat, almost coming back up to standing in some cases. Check out the jump starting at 1:07 in the video for an example of what I mean. That represents a clear and direct follow-through on the spiral of the jump; riding the momentum rather than stopping it. Incidentally, we discussed similar ideas of shaking off the fear and riding the momentum of a technique with Shawn Johnson’s balance beam routine several years ago. Perhaps that’s why they often describe great athletes as ‘fearless’!

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Concept Spotlight: Non-Doing

There’s a (probably apocryphal) story that Alexander teachers like to tell. It harkens back to the early days of Alexander’s first training course, and it goes like this:

One day on the training course at Ashley Place, the students were all sitting around watching Alexander giving a lesson to one of their colleagues when the doorbell rang. The students were all inhibiting beautifully – and nobody got up to answer the door. The doorbell rang and rang because everyone was too busy inhibiting to get on with doing what needed to be done!

This story reminds us that inhibition should not be a prolonged thing, a state of being; it’s a momentary pause that allows a decision to be made in the form of direction. Inhibiting doesn’t mean never doing anything at all; at some point, you’ve got to get on with it! The important thing about inhibition is the pause itself; if you’ve paused for a moment to think about how you plan to do something, you’ve successfully inhibited and you can now go about your day.

Non-doing, on the other hand, is more like that state of being. It’s being open and receptive enough to allow the inhibition to happen when it’s needed, and then carrying that openness through to allow movements and actions to take place. Inhibition is a tool to use when needed, but non-doing is a state of mind that allows that inhibition to be effective. For example, inhibition is pausing for a few moments after your friend who has just poured out their heart to you says “What do you think?”, to marshal your thoughts before responding. Non-doing is being open and patient enough to actually listen to their entire soliloquy with earnest interest and refrain from thinking about how to respond until they ask.

It’s easy to misconstrue inhibition as the perpetual prevention of everything habitual, the repeated reminding of yourself not to react to every single stimulus that you perceive – like the ringing of the doorbell at Ashley Place. But if you inhibited that hard about everything, you’d never do anything but sit quietly for the rest of your life! Better to adopt an attitude of non-doing; just stay free enough to allow what needs to happen, to happen without your interference, and give yourself permission to make a decision and follow through on it. As Alex Murray says, “Decide what you’re going to do and then do it, and the rest be damned!”

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Quote of the Month: August 2016

“To have great pain is to have certainty; to hear that another person has pain is to have doubt.”

~The Body In Pain, by Elaine Scarry

I’ve just started reading this book after one of my favorite authors recommended it. It’s a fascinating look into the connection between pain, power, voice, and society, and it might become the subject of a book review later this year. It’s a dense, slow read, and I have a lot of complicated thoughts about the author’s views, some of which are compatible with AT and some of which are emphatically NOT (her view that the body and the self are two separate entities, for example). But I was struck by this quote, because I’ve been thinking a lot about pain already from talking with my students.

In the introduction to her book, Scarry says this in the context of the issue of what she calls “the inexpressibility of pain.” Physical pain is a curious experience, because it is undeniably present if you are the one in pain – sometimes to such a degree that it is hard to think of anything else – but it’s also practically impossible to articulate verbally in a way that someone else will truly understand. Nobody else can ever be inside your body, so nobody else can experience your pain. The best we can do is to use analogies to describe the pain and hope that the person listening can empathize.

Doctors know this problem well; it is the reason the dreaded “pain scale” has emerged – rank your pain on a scale of one to ten – how bad is it? This method only describes the intensity of the pain, though, and it is incredibly subjective since it’s based entirely on the patient’s individual pain tolerance. Other scales have been offered which focus on ranking pain based on how much it interferes with your normal activity, which is better – but still, it leaves the asker trying to imagine what it must be like to be in that level of pain. I often ask students to describe their pain, to help me pinpoint possible culprits in their use, and I usually ask more than just intensity. I’ll ask about quality of pain – is it a shooting, acute pain or a dull aching that doesn’t go away? I’ll ask about context – does it pop up more when you do certain activities, or do you notice it go away at any specific times?

For me, this inexpressibility of pain reminds me of the inexpressibility of a lot of AT experiences – I often tell students ‘you might not be able to explain what it feels like; you don’t really have vocabulary for it yet.’ We tend to think in narrative, and so feel compelled to explain our sensations in words, as a story we can tell another person. For this month, I’m thinking about sensations that can’t be explained in story – I encourage you to join me!

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Concept Spotlight: Inhibition

I’ve been talking a lot with my students recently about the Alexander concept of “inhibition.” I originally posted a Concept Spotlight about Inhibition back in 2011, but it’s one of the most important concepts in AT, and as such certainly bears repeating.

One of Alexander’s main principles is that habits are so thoroughly ingrained in us that all it takes is the mere thought of a course of action to send us halfway into a habit. Remember, for Alexander a habit is defined as a conditioned response to a stimulus, so merely thinking about the stimulus itself can send us into the habit right from the beginning. If we attempt to correct a habit after noticing that it is already happening, we will be so far into the pattern that change at that point is nearly impossible. In order to change the habit, we must go all the way back to the instant the stimulus is given, and stop the habit before it starts. This is where Alexander’s “inhibition” comes in.

Think of inhibition as a game of Simon Says. You are given an order, such as “please take a seat.” Since Simon didn’t say to do it, you withhold your action, refusing to allow yourself to start a habitual movement pattern. In a practical sense, you stay standing. This opens up space for you to make a choice about HOW to complete the action. If you just sit without thinking, you’ve lost the game. In an Alexander Technique lesson, the teacher works with you to hone your skills at this Simon Says game until you yourself can play both parts, giving orders and at the same time withholding action upon them until you’ve made your choice.

If you’ve ever played Simon Says, you’ll quickly realize that the idea of playing it by yourself doesn’t really make sense, since you know the order is coming and are not actually reacting in the moment in the same way as when the order is external. This is why it’s so hard to practice the process of inhibition – you have to catch yourself in the moment. Practicing in a lesson inevitably feels forced, since your teacher has informed you ahead of time of the incoming order. Like much of the Technique, you can only really arrive at inhibition indirectly. My general strategy, therefore, is to assign the student inhibition ‘homework’ rather than working directly with it during lessons.

One of my favorite non-Alexander quotes is from Socrates, who said, “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” Inhibition is like that; it’s learning to entertain a thought without your whole self jumping to embody it.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.