Quote of the Month: July 2014

“When you stop doing the wrong thing, the right thing does itself.”

This quote for me is a great example of just how well Raymond Dart’s developmental movement work ties in to the Alexander Technique. The human body, on some level, innately knows the most natural and efficient way to move. You can tell this by watching any baby or toddler learning to walk; they aren’t consciously thinking about how to stand, their bodies just find the right way naturally. As we age and begin to fit into society, we stop listening to our bodies and start second-guessing ourselves. We begin to feel self-conscious about one thing or other, and try to “fix” it by placing affectations on top of it. But none of these added habits are ever going to actually fix the perceived problem. The only way to truly return to our developmental ease is to begin to strip away the bad habits, to stop doing the wrong things. When the habits have been removed, the body’s natural ease and efficiency will kick in, and the right thing will quite literally “do itself.”

It’s interesting, and I feel important, to note that this concept is equally valid for mental and emotional habits. Notice I said “perceived problem” earlier? We all make constant judgements about ourselves and others, and these judgements can be detrimental to our overall well-being. You are your own worst critic, and it’s very possible that the problem you are so hung up over is not at all what is actually going on, nor even what anyone else sees. The idea of stopping the wrong thing can apply just as easily to stopping habits of negative self-talk – when was the last time you looked at yourself in a mirror and actually stopped yourself from thinking anything negative about what you saw? Learning to stop these “wrong thoughts” can have a dramatic effect on the way you perceive yourself and the world around you.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

A few months ago I talked about Developmental Movement and the work of Raymond Dart. There are many ways that Alexander teachers can incorporate Dart’s work into lessons, but the one that appeals the most to me is the idea of what I call “the building blocks of movement.” Today I’ll be discussing two of these building blocks: Primary and Secondary Curves.

First, it’s important to remember that the spine is not a straight line; there are natural curves in the spine, both forward and backward. These curves allow it to function as a sort of spring or shock-absorber, and give it the flexibility to be able to adapt and respond to movement. These curves appear at the very beginning of the developmental process, and as such we refer to them as Primary and Secondary curves.

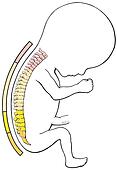

While in the womb, the spine of the fetus needs to be curved in order to fit into such a tight space. If you look at an illustration of a fetus in the womb you’ll see that the spine is curved forward, bringing the front side of the body closer in on itself. Since this pattern is the first one that develops, we refer to it as Primary Curve. Any movements we perform as adults that tend towards this forward curve are reflections of that building block of Primary Curve.

While in the womb, the spine of the fetus needs to be curved in order to fit into such a tight space. If you look at an illustration of a fetus in the womb you’ll see that the spine is curved forward, bringing the front side of the body closer in on itself. Since this pattern is the first one that develops, we refer to it as Primary Curve. Any movements we perform as adults that tend towards this forward curve are reflections of that building block of Primary Curve.

When a baby is a newborn, they cannot support their own head. This is because the muscles in the back of the neck haven’t begun to engage – what we sometimes refer to as “plugging in.” Once those muscles begin to engage, the baby can start to look up and around, and support their own head.  This looking up from the floor gives the beginning of what we call Secondary Curve – the spinal extension that tends towards an arched back. We refer to it as Secondary because it is the second basic movement pattern that we learn as babies. As adults, any movements that tend to arch our back are reflections of Secondary Curve.

This looking up from the floor gives the beginning of what we call Secondary Curve – the spinal extension that tends towards an arched back. We refer to it as Secondary because it is the second basic movement pattern that we learn as babies. As adults, any movements that tend to arch our back are reflections of Secondary Curve.

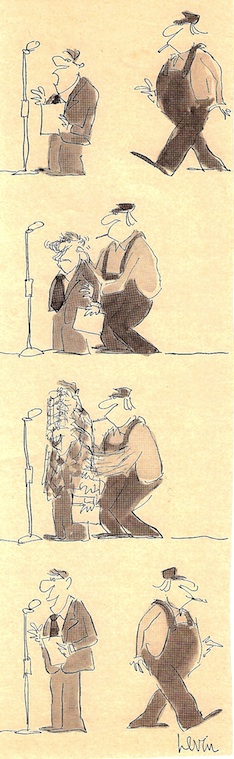

As an Alexander teacher, I use these building blocks to help students break down complex movements into combinations of these simple ones. It becomes particularly useful with students who have physical careers, such as dancers, martial artists, atheletes, etc. If a student is having trouble with a particular movement, we’ll often look at it from a perspective of Primary and Secondary curves, identifying whether the movement should tend towards Primary or Secondary, and whether the student’s performance of the movement is actually working with these building blocks.

A ballet dancer who keeps falling out of her back attitude might find that her spine is tending toward Secondary, when what she really needs is to tend towards Primary in order to counterbalance the elevated back leg. A modern dancer might find that his high release improves when he thinks of the full connection and direction of a Secondary curve rather than simply crunching back onto his lumbar spine. A martial artist might find that the weight of her sword overhead is causing her to fall backwards, and she needs to tend more towards Primary to counteract that.

A ballet dancer who keeps falling out of her back attitude might find that her spine is tending toward Secondary, when what she really needs is to tend towards Primary in order to counterbalance the elevated back leg. A modern dancer might find that his high release improves when he thinks of the full connection and direction of a Secondary curve rather than simply crunching back onto his lumbar spine. A martial artist might find that the weight of her sword overhead is causing her to fall backwards, and she needs to tend more towards Primary to counteract that.

Next time, we’ll discuss another of the building blocks of movement: spirals.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Quote of the Month: May 2014

“[Alexander] fundamentally discovered a way of imparting a new experience and it can no more be described than a kiss can be posted.” ~Jeremy Chance, Principles of the Alexander Technique

I came across this quote in the book Principles of the Alexander Technique, which I plan to write a full review of later this month. I love the idea of trying to send a kiss through the mail, and I think it’s a great way of illustrating the problem many teachers face when trying to explain the Technique. After all, how would you send a kiss through the mail? You could write a paragraph describing the sensation or experience of a kiss, or you could put on lipstick and kiss a piece of paper, but neither of those could communicate the experience itself. At its core the Alexander Technique is a physical, mental, and emotional experience, much like the experience of a kiss, and it’s incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to articulate an experience in words.

I’ve often heard it compared to explaining yellow to a blind person, or describing music to someone who has never heard it. How would you explain a color to a blind person – color exists only in the visual plane! You could describe the feeling you get when you look at the color, or some common items that are that color, but none of that would actually inform them of what that color looks like. Alexander Technique is much the same, but in the physical, mental, and emotional plane instead of the visual. By definition, the student has no context for the new experience they are being given. This is in fact the point of the work. With no context you are less likely to fall into your old habits, so a teacher can give you the experience itself and then give you the context to go with it, generally in the form of new vocabulary and verbal directions.

I often warn my new students that the verbal directions I’ll be giving may not make a whole lot of sense – and let them know that that is by design. As teachers, we try to select verbal phrases that you won’t already have a physical association with, so that we can give you a completely new experience rather than trying to replace the old one. It’s easier to simply let go of the idea of “sitting up” and think about something new instead than it is to try to connect the idea of “sitting up” with a new physical experience. It’s not “sitting up” anymore; it’s this other thing now – and the vocabulary to communicate that new thing will usually be supplied by the teacher. People who haven’t experienced the Technique before probably have no idea what “a gentle pull from the wrist to the elbow” would really feel like, since they’ve never really thought about it. A teacher will give that direction and immediately follow it up with a physical experience of what that direction actually means, using her hands to communicate what her brain has no words for.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Everyday Poise: Ambam the Gorilla

There’s a gorilla at a British zoo who walks upright like a human. His name is Ambam, and he’s been all over youtube since he first started walking upright a few years ago. Check out this video:

Ambam strikes me as a very clear picture of the process that humans likely followed in switching from anthropoid (walking on feet and knuckles – like a gorilla) to full bipedal. He’s in the middle of the transition, and so we can learn a lot about our own use by watching him. Let me point out a few specific things that we can see in the video above.

First, check out his standing use (starts about 10 seconds in). If you look closely, you’ll notice that his hips are pressed forward a bit, and he seems to have a little bit of a hollow in his lower back. You can see this in the wrinkles and folds of his skin in the area between his hips and ribs in the back. This is an exaggerated version of a pattern I see in a lot of students, where the hips are pressed forward and the back is collapsed down. My theory on this pattern is that it’s comfortable because we’re basically resting on our bones – pushing the hips forward takes the hip sockets to the end of their range of motion, where they can lock into place, and collapsing down in the back allows the spine and ribs to sort of “sit” on the pelvis. One of the misconceptions that I end up discussing with a lot of students is the idea that releasing tension is not the same thing as letting go of all your muscles. If you actually let go of all your muscles, you’d end up in a puddle on the floor. So to remain upright while letting go of all your muscles, you are forced to rely on your skeletal structure to support you, which puts you into this position of hips pushed forward and back collapsed down. Ambam in this video is a particularly good illustration of this because he has just recently started walking upright. He doesn’t possess the muscle tone necessary to support his back in this upright position, because he hasn’t been doing it long enough to develop that tone. So his body is forced to settle onto its skeleton, giving us that same pattern.

Now let’s look at his walking use (starts about 28 seconds in). He’s a bit pitched forward from the hips (probably a remnant of walking on his knuckles, when his back would be forward from his hips), and he sways side to side a fair amount, but you can really see that his head is leading him forward. His head, neck and back are in a well-coordinated relationship, even when performing a movement that his body has not yet adapted to doing. Alexander would say he has a very clear Primary Control. This slight pitch forward is much more useful for walking, since while in motion he can’t simply rest on his bones. We could even think of this as a slight overcompensation for the collapsing back that he does while standing. What he needs (and what we need as humans) is to find a happy medium between the two.

One last point – when the reporter asks his keeper why he thinks Ambam might have started walking like this, the keeper points to the fact that when Ambam is walking in that footage, he is carrying a log in each hand. The keeper posits that Ambam realized that walking upright allowed him to walk with his hands full, and thus gives him more options for movement and more potential for growth and development. The next time you see a small child learning to stand, pay attention to the intent behind their movements. A few years ago I was visiting with a friend while her young daughter played on the floor. The last time I had seen her, the daughter was at the developmental stage of clambering up to standing, needing to hold on to something to stabilize herself but able to get onto her feet. In this visit, I watched her go into a squat on both feet, and use her leg muscles to bring her up to standing with a deliberation that hadn’t been present on their last visit. But what was the most intriguing about this movement was the obvious intent behind it. She, like Ambam, had a toy in each hand, and clearly wanted to stand up and bring them over to mommy but didn’t want to have to put them down in order to get up. So her leg muscles “plugged in,” and she was able to stand without using her hands. It is this kind of clear intention that is so apparent in babies and young children, and seeing it present in Ambam’s decision to walk upright suggests that this intention may be the driving force behind all major developmental milestones, not just on a personal level, but on an evolutionary level.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Concept Spotlight: Constructive Rest

Sometimes we get so caught up in our lives that we never really get a rest. Even on our down-time we worry about what happened today or what will happen tomorrow, and our sleep becomes plagued by anxiety dreams. It is at these moments that Constructive Rest can be the most beneficial.

The Alexander Technique does not have exercises, so when a student asks what they can work on in between lessons, there is often not much to say. Constructive Rest, however, is something beneficial that a student can do for themselves in between lessons.

In Constructive Rest, you simply lie on your back on the floor, feet planted, knees up, with your head supported by a stack of 1 to 3 paperback books. Your hands can rest on your hips or ribs or you can fold your arms over your stomach, wherever is most comfortable. This position is known as “semi-supine” and is essentially the same position you are in when lying on the table during a lesson.

In Constructive Rest, you simply lie on your back on the floor, feet planted, knees up, with your head supported by a stack of 1 to 3 paperback books. Your hands can rest on your hips or ribs or you can fold your arms over your stomach, wherever is most comfortable. This position is known as “semi-supine” and is essentially the same position you are in when lying on the table during a lesson.

Why the books under the head? Well, if you look at a skeleton in correct alignment, you’ll see that the back surface of the head is not even with the back surface of the back; it’s a bit further forward than the back. If you lie on the floor without a support for your head, you immediately throw the rest of your alignment out of whack. The books support your head and allow your spine to release into beneficial alignment. Your chin is a good indicator of whether you have an appropriate amount of books; if you feel like your chin is pressed back into your throat, you need another book. If you feel that your chin is pushing forward into space, try removing one book or finding a narrower book. You should feel released evenly at the front and back of the neck. The number of books required is different for every individual, and may even differ for the same person day to day – do this in your library so you have an assortment of books near to hand!

Why the books under the head? Well, if you look at a skeleton in correct alignment, you’ll see that the back surface of the head is not even with the back surface of the back; it’s a bit further forward than the back. If you lie on the floor without a support for your head, you immediately throw the rest of your alignment out of whack. The books support your head and allow your spine to release into beneficial alignment. Your chin is a good indicator of whether you have an appropriate amount of books; if you feel like your chin is pressed back into your throat, you need another book. If you feel that your chin is pushing forward into space, try removing one book or finding a narrower book. You should feel released evenly at the front and back of the neck. The number of books required is different for every individual, and may even differ for the same person day to day – do this in your library so you have an assortment of books near to hand!

The idea behind Constructive Rest is that you simply rest, lying quietly and bringing your awareness to where you feel excess tension in your body. The semi-supine position is advantageous to the body, so that resting is constructive in and of itself – you don’t need to do anything; your body will slowly return to its full length and width as gravity works to your advantage. The accepted theory is that after about 12 minutes, gravity will have given you back the full space in between your vertebrae and allowed the cartilage in your body to expand back to its full state. The general recommendation is that constructive rest should last for 15-20 minutes, about once a day, though the more often you can do it, the better.

My senior year of college I did a special individual project on the Alexander Technique. As part of this project, I decided that I would do ten minutes of Constructive Rest before every single class I took all semester, whether it was a dance class or an academic. I rested in the studio before each dance class, and I rested on the floor of my dorm room before leaving for each academic. I initially chose this because it was something tangible that I could do regularly for my project, but I was surprised to realize just how much I was getting out of it as the semester went on. I began looking forward to my next resting period, the next chance to let the worries of the day filter away from me and reconnect with myself and my present state. During a show week in the dance department, my regular resting kept me sane. I wrote in my journal that “it’s kept me from getting tangled up in the past and the future, and keeps me more firmly in the present.” I began to work constructive rest into my pre-show routine. To this day, I still use constructive rest when I feel myself getting too caught up in life, as a chance to re-center and reconnect with myself and my awareness.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Quote of the Month: April 2014

“You can only look forward as far as you can look back.” ~Raymond Dart

Continuing the theme of developmental movement month here at Forward and Up, here is one of my favorite quotes from Raymond Dart. This is something that he said a lot while working with my teachers, Joan and Alex. He used it as a rationale for learning about developmental movement, the idea being that you can’t really make progress unless you are aware of the conditions that brought you to this point. In Dart’s mind, the farthest you can look back is the fetal curve, the position you were in inside the womb. His developmental movement work all starts with fetal, exploring the patterns that developed out of that tightly-coiled shape and the natural progression from birth to crawling to standing. Through working in fetal, you gain an increased understanding of just how far you’ve come, and how much forward progress is still available to you.

This quote is equally applicable to the basics of Alexander Technique as well. Again, you can’t change a habit and move forward until you’ve looked back to see what might have originally caused it. To illustrate this, let me tell you a story I tell a lot of my students. In my last year of training, one of my fellow students was in the middle of a lesson with Joan when he had an epiphany of sorts. As she moved him in the chair, a sudden look of realization crossed his face, and he told us a story: Back when he was 8 or 9 he was sitting one day eating an apple, holding the apple in his left hand and using a paring knife to cut slices off the apple with his right. His hand slipped, and he sliced through the webbing in between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand. “As soon as it happened, my reaction was this” – telling us the story, he suddenly clutched his left hand with his right and curled his whole body in around it, as if protecting it. “And I just realized – I’ve been doing that ever since!” The reaction was so sharp and traumatic that his entire left side was still holding the remnants of that tension so many years later. The epiphany he’d had was those muscles finally releasing that tension, which called the memory to mind (a phenomenon that happens a lot when habitual muscle tension is finally released). Muscle tension is often linked to past events, and once we look back to see where the tension comes from, we can begin to release it and look forward again.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Secrets of Alexander Technique, by Robert MacDonald and Caro Ness, is one in a series of illustrated pocket-guides to alternative therapies. Clocking in at barely three-inches square and less than an inch thick, I expected this book to leave something to be desired, probably glossing over the more complex points in favor of a feel-good self-help guide. I was pleasantly surprised to find that I was completely mistaken. Secrets serves as a shockingly detailed and thorough introduction to the Technique, centering around the theme of self-awareness and choice. The book argues that posture is an expression of self, and by using the tools of increased self-awareness and choice that the Alexander Technique provides, we can achieve our fullest potential.

The book itself is remarkably broad in scope, covering a whole host of topics I didn’t expect a book of that size to get around to. Simple, concise explanations give meaning to Alexander’s often-confusing words, and terminology is introduced so naturally that the reader doesn’t even realize how strange the terms themselves are. Illustrations are plentiful and smartly used, never becoming too distracting but instead assisting in communicating the book’s message. Each turn of a pocket-sized page introduces a new topic, providing bite-sized bits of info on a wide range of subjects. During the second half of the book various applications for the technique are discussed, and the book maintains the same organizational structure for each application: discussion, energy diagram, turn the page, photos of students exploring the application. This regular structure allows the reader to see the similarities between the various applications, as well as the things that make each one unique.

Despite a thesis statement that sounds a bit like new-age mumbo-jumbo, Secrets is a surprisingly strong and thorough introduction to the Technique. The book constantly returns to the idea that lessons are what help with various topics, emphasizing the need for a teacher to help the student fully understand and internalize the concepts. The descriptions are amazingly concise, and yet amazingly thorough. As I read, I found myself continually impressed, often writing in my notes “nice to see that discussed” or “still managed to address that”. Frequently I would marvel at the skill with which the author is able to communicate a tricky-to-define physical experience, such as describing means-whereby as an “art” or the frequent use of the phrase “alert stillness.” The one-topic-per-page structure is innovative, unique, and very effective. It makes the book easy to pick up and put down and helps to keep things simple, preventing the reader from getting bogged down in semantics. Each turn of a page brings a new thought or idea, which is introduced simply, illustrated helpfully, and tied neatly back in to the main principles – just in time to turn the next page.

While a very strong showing overall, Secrets is not without its flaws. Occasionally the book uses phrasing that makes me a bit wary, such as beginning a direction with “Don’t…” or suggesting what the reader might be feeling. These moments are few, though, and they are always described thoroughly enough for me to be satisfied. Surprisingly for such a small book, there are no significant omissions. Even aspects of the technique such as breathing and gravity-resistance, which are often ignored in an introduction, are acknowledged and given their own two-page tidbit. A variety of applications from running to typing to swimming to Tai Chi are covered in the second half, with comparisons and illustrations that make it easy to extrapolate to the reader’s particular favored activity.

Overall, Secrets of the Alexander Technique is an excellent introduction to the principles and practice of the Technique. I would recommend it to most new students, particularly those coming to the technique from a wellness or betterment-of-the-self mentality. I might not recommend it as much for a skeptical student, since it does not spend as much time discussing the practical results of lessons (reduction of pain/tension etc.) as some other books, and the moments of new-age-y feel might turn off a skeptic. However, for anyone not staunchly skeptical I’d highly recommend it as a first read.

The Nitty-Gritty

Title: Secrets of Alexander Technique

Author: Robert MacDonald, Caro Ness

© 2001 by Dorling Kindersley Publishers Ltd

ISBN-10: 0789467720

ISBN-13: 978-0789467720

Status: Used copies on Amazon

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Everyday Poise: Brachiation

When discussing Developmental Movement, we can look at “development” in multiple ways. While the most obvious aspect is babies learning to crawl and walk, creating the movement patterns they will use in life, we can also look at Developmental Movement on an evolutionary scale. By studying other primates, we can learn more about our own use and our own bodily efficiency. Today I’d like to discuss one aspect of this evolutionary developmental movement: brachiation.

But first, watch this video of a gibbon swinging through the trees.

The term “brachiation” is derived from the latin word for arm – brachium – and refers to swinging through the trees using only the arms. Children on monkey bars in a playground are technically practicing brachiation, and research suggests that we humans may have had an arboreal ancestor who traveled through the trees using this technique. If you look closely, you’ll notice that the gibbon reaches for the next branch with the outside edge of his hand and arm – the first thing to grasp the branch is his little finger. This reaching with the outside edge of the hand is one of the defining characteristics of brachiation, and it seems to be one of the major techniques that we humans have lost in descending from the trees. When we reach for something, we usually extend our index finger and thumb towards it. Why would a primate reach with the little finger, rather than the index finger and thumb as we humans do?

It may surprise you to learn that the strongest part of the hand is actually the pinkie-side, not the thumb. The muscles of the little finger connect through to muscles in the outside of the forearm much more strongly than those of the thumb side, meaning that the pinkie-side of the hand has a much more direct connection to the support muscles of the back and scapula. If all you’ve got supporting you is your hand, you’re better off grasping with the pinkie – it’ll give you a much more stable hold. This is the reason why martial artists who use weapons hold the weapon most tightly with the pinkie and most loosely with the index finger – it’s a stronger and more stable hold. Incidentally, martial artists refer to this hold as the “monkey grasp” – and no, that’s not a coincidence.

This concept of brachiation can be extremely useful for humans, particularly when reaching for an item above head level. By reaching with the pinkie first, we can keep the shoulders released and the support muscles of the back engaged, allowing for better control of the object once picked up. Just as it’s easier to carry a heavy load by getting underneath it than by hauling straight up from above, reaching with the pinkie connects through to the back and allows the muscles of the scapula to do the work from underneath, rather than relying on the upper deltoids to haul up from the top of the shoulders. This not only makes it easier to lift the weight in question, it also makes it easier to lift the weight of the arm itself.

Next time you go to a zoo, take a trip through the primate house and keep an eye out for brachiation. Watch how easily they move through their habitats, and look for the pinkie-side of the hand!

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Every Alexander Technique teacher has a unique style of teaching, one that has grown up organically around their previous experiences with the Technique and with life in general. My teachers, Joan and Alex Murray, are a great example of this. Joan was a dancer with the royal ballet, and Alex was flautist with the london symphony. Joan’s teaching style is more dynamic and focuses more on movements into and out of various positions, while Alex’s is more poised and still, and focuses more on breathing and philosophy. One thing their teaching styles have in common, though, is the inclusion of concepts of developmental movement, influenced by the work of Australian anthropologist Raymond Dart.

Joan and Alex spent time working with Dart as he worked out his concepts of Developmental Movement, and seeing connections between his work and the work of Alexander, they began to incorporate the developmental movement procedures into their teaching. Developmental Movement work is the study of the natural ways that we learn to move as infants, from rolling over to crawling to standing and walking. The idea behind the pairing is that the way we learn to move naturally as babies is generally the most efficient way for our bodies to function, and re-learning these movements is therefore a good insight into increasing our standard of functioning. Dart invented a series of movements called the “Dart Procedures” that take a person from lying on the floor in a fetal position all the way to standing, using a series of motions that our bodies perform unconsciously as infants. These movements make use of the basic patterning systems of the body, from homologous (upper body vs. lower body) to homolateral (right side vs. left side) to contralateral (right arm to left leg and vice versa), in roughly the order that children discover them. The Murrays’ variation of Alexander Technique incorporates these patterning ideas, along with the concepts of primary and secondary curves combining to form spirals, to analyze everyday movements looking for ways to conceptualize them efficiently.

The concept of Developmental Movement can also be explored on an evolutionary scale, discussing the similarities between our movement and the movement of other primates. There is a plethora of information to be found within Dart’s work, so the next few Concept Spotlights will deal with some of the specific sub-concepts individually. Becky and Luc’s book, Dance and the Alexander Technique, also explores the Dart procedures in connection with the Alexander Technique as they relate to dance training and offers quite a bit of practical exploration on this topic. (Click the link above to go to my review of this book.)

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Practical Movement Control, by Jack Vinten Fenton, concerns the need for a solution to the growing number of adults experiencing undue anxiety and tension as a result of poor bodily use. The central theme of the book is that many of our current stresses, strains and anxieties are due to an excess of muscular tension, and that this relationship is present even in early childhood, growing more and more pronounced as we grow older. According to Fenton the best solution to this problem is preventative re-education, ideally presented within the context of the existing primary school system. The book appears to be targeted towards education professionals and teachers of young children in particular, showing several concrete ways in which teachers can incorporate the work into their classrooms. Though the word choice occasionally leaves something to be desired, overall Practical Movement Control is a strong and succinct explanation of the principles of habit and change, told through numerous practical examples and research findings.

Practical Movement Control, by Jack Vinten Fenton, concerns the need for a solution to the growing number of adults experiencing undue anxiety and tension as a result of poor bodily use. The central theme of the book is that many of our current stresses, strains and anxieties are due to an excess of muscular tension, and that this relationship is present even in early childhood, growing more and more pronounced as we grow older. According to Fenton the best solution to this problem is preventative re-education, ideally presented within the context of the existing primary school system. The book appears to be targeted towards education professionals and teachers of young children in particular, showing several concrete ways in which teachers can incorporate the work into their classrooms. Though the word choice occasionally leaves something to be desired, overall Practical Movement Control is a strong and succinct explanation of the principles of habit and change, told through numerous practical examples and research findings.

The book deals with the relationship between excess tension and various forms of misuse, from early childhood through the young working adult. Beginning with a discussion of the principles of the Technique (though he does not mention Alexander’s name until much later), the book continues through a description of the author’s research projects involving schoolchildren of all ages and their use during an assortment of basic activities. The book then discusses how to achieve good use and provides suggestions for ways to teach the material in schools. Throughout the book Fenton uses findings from his research studies to illustrate his points, making effective use of a plethora of charts, photographs, and figures. This emphasis on concrete examples would likely be helpful for a student who is skeptical of the validity of the claims made by Alexander teachers.

This emphasis on examples and research is one of the strong points of Practical Movement Control. Fenton’s explanation of the principles of habit and change is both straightforward and persuasive, and every phase of discussion is accompanied by a chart or illustration that works to sweep away any uncertainty and show the principles to be justified and supported by his research. In addition, Fenton does not even mention Alexander until more than halfway through the book, and even then it is only one glancing mention of “the work of FM Alexander.” This adds to the reader’s perception of the book as something related to but separate from the Alexander Technique. It may have been inspired by the work of Alexander, but Practical Movement Control is Fenton’s work, supported by his own research and expressed in his own terms.

Unfortunately, those terms are one of the largest weaknesses of Practical Movement Control, at least from an Alexander perspective. Throughout the book, Fenton uses terminology that Alexander teachers deliberately try to avoid, such as words like “relax,” “posture,” and “positioning.” While Alexander teachers have very specific reasons for avoiding those words (“relax” implies collapse and lack of muscle tone, “posture” and “positioning” both imply a fixed position rather than a dynamic relationship), Fenton appears to be attempting to discuss the principles using language that was commonly used at the time; perhaps he felt it would be easier for his readers to understand. In addition, while he does mention the concept of thought setting up tension patterns, he doesn’t fully draw attention to the implications of thinking versus doing that are so central to the practice of the Alexander Technique, and are the precise reason why word choice is so important when working with habit. His message communicates clearly nonetheless, and is still a persuasive argument, but it is missing a crucial corner of the philosophy of the Technique.

In conclusion, Practical Movement Control is a succinct introduction to the principles of habit and change, and would be a fairly good introductory read for someone who tends to be skeptical of the power of habit and faulty sensory appreciation. The plethora of concrete evidence would do much to convince a skeptic, however it should not be used as a stand-alone. The student would need to be made aware of the shortcomings in the book, particularly in word choice and the way thought influences tension patterns. I would recommend this book to a schoolteacher or professor interested in how they can pass the information along to their students, but only after they have had a foundation of several lessons.

The Nitty-Gritty

Title: Practical Movement Control

Author: Jack Vinten Fenton

© 1973 by MacDonald And Evans LTD.

ISBN: 0-8238-0145-4

Status: Possibly Out of Print, a few used copies on Amazon

Aliases: Published in the UK as “Choice of Habit”

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.