Quote of the Week 9/19/11

“Dare to let it feel wrong. Take a chance on letting me give you an experience that you don’t think is right. When you walk out of this room you can always go back to what feels right. But right now, you’re allowing both of us the luxury to make a mistake.” ~Judith Leibowitz

I love this quote because it reminds us that it’s okay to make mistakes, to be wrong. I love the idea of daring to be wrong, since so much of our culture revolves around being right. When we start a new job or learn a new skill, we want to be good at it. We don’t want to make a mistake since we’re trying to prove ourselves, and often to people we’ve just met at that. But Ms. Leibowitz’s quote reminds us that an Alexander lesson is a positive and supportive place, where teacher and student can both dare to be as wrong as they like.

In a lesson, there is no such thing as “wrong” or “right,” there is simply “different,” and this judgement-free atmosphere gives us the luxury, as she puts it, to make mistakes without worrying about the consequences. Because what consequences are there in a lesson, really? What’s the worst that could happen? You feel strange. Maybe you fall over because you’re not used to moving a certain way. You bump up against a mental habit you didn’t know you had and find yourself thinking surprising things. In a lesson, all that is okay. You can use the time to sort yourself out, figure out who you are now, and how that might be different from who you were when you walked in. And when the lesson is over it’s okay to go back to your old habits, to do what makes you comfortable. Just give the new experiences room to introduce themselves, and then do with them whatever you wish.

As we discussed last time, the act of stopping to think is known in the Alexander Technique as “inhibition.” One of Alexander’s main principles is that habits are so thoroughly ingrained in us at this point that all it takes is the mere thought of an action to send us halfway into the habit. If we attempt to correct a habit after noticing that it is happening, we are already so far into the pattern that change is nearly impossible. In order to change the habit, then, we must get right back to the instant the impulse is given, and stop the habit before it starts. This is where Alexander’s “inhibition” comes in.

Think of inhibition as a game of Simon Says. You are given an order, such as “please take a seat.” Since Simon didn’t say to do it, you withhold your action, refusing to allow yourself to start a habitual movement pattern. In a practical sense, you stay standing. This opens up space for you to make a choice about HOW to complete the action. If you just sit without thinking, you’ve lost the game. In an Alexander Technique lesson, the teacher works with you to hone your skills at this Simon Says game until you yourself can play both parts, giving orders and at the same time withholding action upon them until you’ve made your choice.

That choice is known in the Technique as “direction.” You direct yourself to move in a specific way or take a specific action, consciously and intelligently. In practice, direction is like a sense of energy, tone, or qi, a thought that engages the musculature just a tiny bit, to create life and lightness in the physical structure without creating tension. In the Technique we focus on how small the direction really is, and how the mere thought of a movement can create the tone and energy without the student trying to help at all. Often a teacher will give a direction, such as “think of your head going forward and up,” and will follow it almost immediately with “just the thought.” This is because when told to think of something, we will all instinctively start to do it, even just a little, out of that old desire to be right and to show that we are listening and trying to do as we’re told. Studying the Technique is about becoming more and more able to think of a thing without doing it.

One of my favorite non-Alexander quotes is from Socrates, who said, “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” Inhibition is like that; it’s learning to entertain a thought without your whole self jumping to embody it. At that point, you can decide for yourself what direction you want to go.

Quote of the Week 9/12/11

“Decide what you’re going to do and then do it, and the rest be damned!” ~Alex Murray

One of the main principles of the Alexander Technique is the need for transferring decisions from the subconscious plane to the conscious one, in an act that Alexander referred to as “inhibition.” Inhibition in the Alexander sense refers not to suppression or restriction, but rather to the voluntary withholding of impulsive actions. When confronted with an action that is usually performed subconsciously (such as getting out of a chair), Alexander challenges us to simply stop and think about HOW we intend to complete the action before attempting it. By stopping to think, we create choice where there was habit, and open ourselves up to the ability to complete old actions in new ways.

One of the drawbacks of creating this choice, however, is that doubt, self-consciousness, and the ever-present desire to be “right” can creep in and lodge in the space created by the choice. This frequently bogs down the student, as they feel a great responsibility to always employ correct use and to never “slack off.” My teacher, Alex Murray, deflects this feeling with this oft-invoked quote. Once you’ve created the choice, simply decide what you’re going to do and then do it, and to hell with the consequences.

Over and over I’ve heard teachers say that the moment they finally clicked with the Technique was the very moment they said “Oh, to hell with it!” and just tried something. Feeling that you must always choose the “right” action is just another sort of end-gaining. The important part is the act of choosing. If you stop long enough to create the choice for yourself, and then make a choice, you’ve inhibited successfully. Whether your decision in that moment was to correct it or to leave it be is irrelevant. (More on Inhibition and Direction in this week’s Concept Spotlight.)

Concept Spotlight: Tension

Ever gone to open a door that looked heavy, given it a good heave-ho, and nearly been yanked off your feet as it turned out to be exceptionally light? You have witnessed first-hand how much unnecessary tension we all carry around with us every day. Try this experiment: go get yourself a cup of coffee (or tea, or whatever hot beverage you prefer). Lift the mug to your mouth, but before you take a sip, look at where your arm is in relation to your body. Most of us will have our elbow at least slightly out to the side; some of you may even have it out so far that your arm is parallel to the floor. Now put down the mug and simply raise your hand to your mouth, as if you were a lovely ingénue in an old movie and you’ve just been surprised. Now look at where your arm ended up. In most cases, your elbow will be down by your side, your arm having moved solely from the forearm down. That is the smallest amount of tension required for the activity of raising the hand to the mouth. So why does the arm go out so far when there’s coffee in it?

There are a multitude of reasons why we might hold excess tension while completing various actions. Many actions are connected with emotions, anxieties, or fears in our brains, and when they are performed, all those anxieties subconsciously act on our bodies, causing them to tense up. Perhaps you have a cup of coffee in the afternoon to soothe your midday jitters. The simple knowledge that you are drinking the coffee in order to calm down may cause you to tense up extra hard until you’ve had those first few sips. After all, if you weren’t tense, why would you need to calm down? If you’re afraid of an action that you must perform, or you’re not confident in your own ability to perform it, you may hold excess tension in an attempt to “get it right” (as we’ve discussed before). In any case, once an action has been associated with a certain level of tension, it can be very difficult to let go of those associations and move with ease.

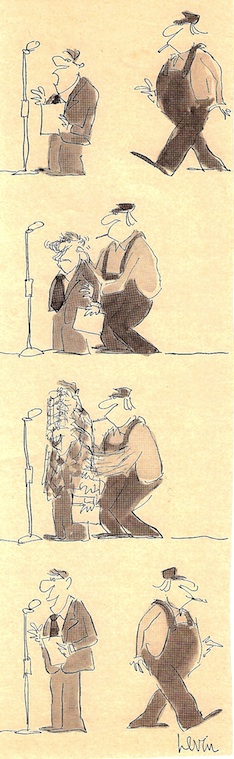

The Alexander Technique gets around this by having the teacher be responsible for moving the student, thus removing the student’s desire to “do” an action they recognize as habitual. In this way, the student is free to simply experience the new ways of moving (and how they differ from the old ones) and in time will be able to allow their body to move in this new way without interfering.

Quote of the Week 9/5/11

“You can translate anything, whether physical, mental, or spiritual, into muscular tension.”

This quote reminds us of just how much our everyday lives affect our physical well-being. Often times we forget to take time for our bodies when we’re busy, and may even forget we have a body at all. But everything you do, whether it’s working long hours to finish a project, stressing about a final exam, or going through a spiritual adjustment, is reflected in your physical self. Often times this manifests as holding tension in one or two very specific spots, usually spots that are overlooked in the natural course of daily life and frequently ones that are particular and consistent to you. It could be your jaw, your abdominals, your calves; just about any muscle group can be a “worry spot.” Finding out where your “worry spot” is can go a long way towards releasing your excess tension.

If your life’s gotten busy or stressful, it is all the more important to pay attention to how you use yourself. Notice where you want to hold onto tension, and see if you can let go, even for just a few minutes. The bigger and more complicated the action we attempt, the more exaggerated our habits become. So you may find that that little bit of tension in your lower back becomes a spasm when you’re working 80 hours a week, or your headaches get worse during a spiritual crisis. It’s just your body’s way of showing you how your actions have affected it. Take a few moments to sit back and release, and your body will thank you.

Note: I’m sorry this post is a day late; I was recovering from moving and sending my friends off on their return trip to Champaign. I could use some quiet reflection on this topic myself these days!

Concept Spotlight: Fear Reflexes

We have such a strong tendency to want to “do what we are told,” as it were, that pretty much anyone when given an instruction will immediately attempt to “do it right.” However, the only thing we have to go on when attempting this is our own sensory appreciation, which as we have already discussed is usually faulty and unreliable. So we become trapped in a vicious cycle of trying to do what feels right and finding it wrong.

Now, not only does failing each attempt to “do it right” reinforce our old habits, but it also brings into play a whole new series of negative emotions along the lines of worry, fear, anxiety, and discouragement. Alexander describes this phenomenon as the “fear reflex;” it’s related to other similar reflexes such as the “fight or flight” response. As a species, we have a tendency to be afraid of the unknown, and when attempting an unknown (such as a new way of moving and using ourselves), we are likely to experience fear in some form (anxiety, nervousness, worry, etc.). These negative emotions cause us to fix and hold and try even harder, and the cycle continues on.

The only way out of this cycle is for a student to decide that rather than trying to be right, he wants to be wrong. (Wrong, that is, by his own standard of sensory appreciation.) With this in mind, a conscious teacher will work from a place not of trying to “get the student to do it right” or “fix the student” but rather of simply giving the student a new experience, and then repeating this experience until it becomes familiar. In this way the teacher, by not asking the student to “do” anything specific, ensures that the experiences the student receives will be pleasant ones, thus inspiring positive emotions along the lines of confidence, satisfaction and happiness. These positive emotions then cause the student to want to receive more of these new experiences, until they become established as new patterns of use.

By the way, I may be late posting next week’s Quote since I’ll be moving into my new apartment in Pittsburgh this weekend. I will attempt to post next week as usual, but I may have to search out some internet access so it might be a bit later than usual.

Quote of the Week 8/29/11

“Everyone wants to be right. But no-one stops to think if their idea of ‘right’ is right.”

Everyone wants to be right. As a species we have a desire to be correct, to do the right thing, to feel as though we are making the right choices and taking the right steps. When given a correction or a task by someone we perceive as important, we are eager to show that we understand and are willing to do it. Unfortunately, this eagerness nearly always manifests itself as “trying to be right.” When asked to perform a task, the instinctive response is to immediately try to do it “right” to satisfy the asker.

However, as we have already discussed on this site, one of Alexander’s main arguments is that we as a species can no longer be sure that what we think is “right” is actually right. Our general level of sensory appreciation has devolved to such an extent that whatever is habitual will feel ‘right’ to us, regardless of whether it actually is. This quote points out that unless we stop and make sure that our idea of “right” is actually right, all the effort in the world will be useless because it will be undertaken using a flawed premise. As every math student knows, if you copy the problem down wrong it doesn’t matter how long you work at it, you’ll never get the right answer. Before diving in, you must stop and make sure you’ve set the problem up correctly, and that your idea of “right” is right.

Concept Spotlight: Habit

Habits are hard to change.

To change a habit, we must react in a way that is different to our usual manner of behaving, and that causes a lot of problems. Most people are unaware that habit is part of the use of the self as a whole, and that if we want to change a habit on a fundamental level, we first have to change the overall use of the self. Eradicating a habit directly will not actually change the behavior, since those patterns are already ingrained in our general use of self. If we attempt to change a habit without changing the whole self, the result will be nothing more than “cure by transfer,” or substituting one bad habit with another that is perceived as less detrimental. Alexander defines habit as the embodiment of all human reactions, as determined by the manner of use of the self. In order to change a habit, we have to change our reaction to the stimulus by changing the way our whole self approaches it.

This task is made difficult by the fact that sensory experiences resulting from habit are often pleasant and feel “right” or “comfortable,” causing the individual to want to continue in the habit in order to continue to receive these pleasant experiences. Furthermore, the attitude of most people towards learning a new activity in order to bring about a desired change is anxiety and a desire to be “right”, coupled with a fear of being “wrong.” In the case of bad habits, however, one’s conception of “right” is wrong. Therefore, any time a person tries to be “right,” he will only be making himself more wrong. To change the habit we have to intentionally do what feels wrong.

The important thing to remember is that change is a gradual process, and cannot be accomplished in one day. Doing what feels wrong results in a disturbing and confusing experience, and so the change must be undertaken slowly to keep those experiences from becoming so strong that they dissuade the student from continuing.

Also, remember that every day is different. What works as the “right” way of standing here and now, in this lesson, was not necessarily “right” for yesterday, nor will it be “right” for tomorrow. It is a process, and the student should allow the change to happen at its own pace, simply following the principles and allowing whatever is “right” for right now to exist and then fall away later on, to be replaced by tomorrow’s “right.” In general, it is found that students have little difficulty in accepting these ideas theoretically, but initially fail in putting them into practice.

Habits are hard to change.

Quote of the Week 8/22/11

“When you stop doing the wrong thing, the right thing does itself.”

This quote shines a light on a common misconception about bad habits. For most people, when they realize they’re doing something wrong, their first instinct is to figure out what to do to correct it. If a dancer is told that she slumps forward in her torso, her instinct (and usually her teacher’s first correction) is to pull her shoulders back. However, in practice it’s found that this doesn’t really correct anything, but merely changes her bad habit to a different “wrong.” She has not returned to a true neutral, but has instead adopted a position of slumping forward with her shoulders pinched together. At its best this may appear to be more neutral on the outside, but in reality it is an incorrect posture that takes twice as much effort and is still just as wrong as before.

To truly remove a bad habit, we have to stop doing the habit instead of trying to correct it. If we can strip away all the layers of habits, we will eventually arrive at the point where the body moves naturally and efficiently, the way it was meant to, and the way it did when we were young and hadn’t yet developed any habits at all. This is why the quote states that the right thing “does itself.” One cannot actively try to do the right thing, since any instance of “trying” simply adds another layer to the habit pile. Once you stop doing all the wrong things, your body will be free to move naturally, and the right thing will happen on its own.

Concept Spotlight: Sensory Appreciation

Sensory Appreciation can be colloquially described as our “sense of feeling.” The information received from the senses, and how we perceive that information, come together to give us a general sense of how something “feels” or “seems” to us. Alexander’s argument is that through the gradual deterioration of our standard of physical use, our sensory appreciation has become unreliable. Whatever we are used to feeling is what will feel “right” to us, regardless of whether it IS right. Therefore, we cannot rely on our feeling to help us make changes, since we can no longer be sure that we are in fact doing what we think we are doing. A man who has always stood pitched forward will feel that he is on the verge of falling over backward when he is really at a true vertical, and a woman with scoliosis may feel crooked and off-kilter when she is really perfectly even.

Since our sensory appreciation cannot be trusted, we must rely on outside observers to tell us whether we are truly where we think we are. Alexander used a three-way mirror and careful observation to make the initial changes to his own use, but students today have the luxury of a teacher to tell them when they are poised and lengthened, and to show them via a mirror when words fail to convince them. In this way, students of the Technique gradually train their sensory appreciation to be reliable again, and can eventually go out into the world secure in the knowledge that what they perceive is true to what is occurring.