For this month’s book review, I read “How You Stand, How You Move, How You Live” by Missy Vineyard. This book appears near the top of Amazon search results for “Alexander Technique,” so I felt it was important to read it since there’s a good chance a potential new student would have purchased it and read it in advance of meeting with me. How You Stand… is an introduction to the Alexander Technique from the perspective of a teacher who is well-versed in neurology and focuses on the scientific aspects of how we think and interact with the world. Despite an innovative and intriguing structure, How You Stand… does have some aspects that worry me.

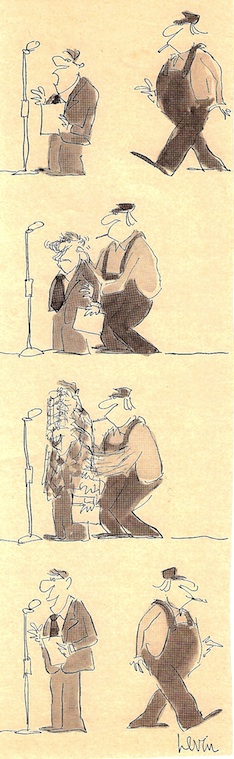

The book focuses heavily on the connection between the brain and the body, presenting AT in a neurological context. The book could almost have been called “How You Think, How You Move…”, since so much emphasis is placed on the way that thinking affects a person’s physicality. The book achieves this through alternating chapters of detailed descriptions of individual lessons and textbook-like discussions of specific neurological processes. At the end of every large section in the book, a chapter of ‘self-experiments’ instructs the reader in ways to attempt to achieve the experiences discussed in the section on their own. Illustrations are used periodically to help communicate trickier use patterns or physical positions, though they appear to simply be illustrated versions of photographs and seemed like an odd visual choice to me. Why not simply include the source photographs?

How You Stand… finds its strengths mostly in the innovative mixture of science and AT. The balance struck me as not unlike AT itself, melding scientific observation and objective knowledge with experiential information to create an overall sense of understanding. My favorite parts were the descriptions of specific lessons, showing the development of a handful of her students over the course of their re-education. Vineyard has a captivating ability to describe her train of thought during a lesson, and to articulate exactly what she’s feeling, seeing, and deciding as she places her hands on a student. For the potential new student, these chapters give a clear picture of what a lesson would be like, and for the teacher, they give new insight into ways to explain the work while in lessons of our own.

The book does have some weaknesses that worry me, however. The self-experiments at the end of each section are the biggest one. I have a similar complaint with these chapters that I’ve had with many ‘self-exploration’ chapters in other books I’ve reviewed in the past – there’s just too much danger of misinterpretation. Giving a self-experiment to the reader necessitates describing things in a “doing” manner, and without a teacher present to ensure the student is still inhibiting and directing, the student is likely to start end-gaining and trying to be right and in the process lose whatever value the experiment may have provided in a lesson setting.

I’m also a bit concerned with her use of the word ‘no’ during inhibition. I was taught by the Murrays to always try to replace negative directions with positive ones, because the very word ‘no’ tends to create a tension response in the student. Saying “I am not tightening my neck” is not as useful as saying “I am letting my neck be free” because the first one is more likely to cause the student to tense up in an effort not to do something.

Finally, it bothered me a bit that Vineyard hardly ever made specific mention of Alexander’s concepts or his terminology. She introduced most of the concepts in her own words, which I appreciated, but she very rarely acknowledged that Alexander had a word for it or discussed his definition of it. She tended to present the work as if it was her own thesis, rather than citing Alexander. And when she did mention him, it was often too little, too late. In my opinion, it should not be 207 pages in before you bring up the phrase “primary control”!

Overall, How You Stand… is a decent introduction to the Technique, provided the reader is currently taking lessons. As with most other books I would recommend that my students skim over the self-experiments and ask me to help them if they find one they’d like to experience, but the neurological context is intriguing and adds a layer of richness to Alexander’s work. In particular, I could see recommending this book to students coming to the work for mental or emotional reasons, since the focus on neurology helps to assuage fears that the student is to blame for the way they react, especially with regard to fear reflexes.

The Nitty-Gritty

Title: How You Stand, How You Move, How You Live

Author: Missy Vineyard

© 2007 by Missy Vineyard, published by Da Capo Press

ISBN-10: 1-6009-4006-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-6009-4006-4

Status: Available on Amazon

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

In today’s Everyday Poise, I’m highlighting a video of a street performer that made the rounds on social media a few weeks ago. Check out his beautiful routine below, and then read on.

EDIT: The original video has been removed, so I replaced it with a new one. It’s not quite the same routine, but most of the same moves are present. The time codes I mention below just won’t be right anymore. Sorry!

Since we’ve been talking about spirals recently, watch it again and pay attention to the focus in his eyes in relation to the direction of spin in his hoop, particularly when he switches from one pattern to another. He controls the spinning of the hoop with his eyes and his whole self; letting his eyes lead him into a big spiral that, because he’s holding on to the hoop, takes the hoop with him into a new pattern. At the very beginning of the routine, where he’s changing patterns a lot, you can see his head always turning in the direction he’d like to go next. In particular, right around 0:50 seconds in you can see him open up from a spin by letting go of his right hand, going into a large beautiful spiral spin, and you can really see the spiral through his whole torso, up and out of his right hand.

Also, remember a few months ago when I mentioned Primary and Secondary curves, and how spirals are a combination of the two? Several times during this routine you can see him working with the shift between primary and secondary as a way of gaining momentum. When spread-eagled inside the hoop, he generally stays tending towards primary, presumably because it’s a more stable direction to sustain, but he shifts into secondary to change shapes or speed up the spin. Right around 1:10, he does a pattern alternating between picking up one foot into what I’d call an arabesque and placing it back down on the hoop. The extensions are beautiful secondary curves, and the placing of the foot back down brings him back into primary. Put together, these two create a very natural way of generating the momentum to keep the spin going. Overall, this performance showcases the idea of spirals as the building blocks of movement, and shows just how powerful a tool they can be when you allow them to move you.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

AT in the News!

Just a quick update to share an AT news story that’s been circulating around social media for the past few days! The Mirror did a roundup article on a bunch of “alternative” treatments for back pain, and they found that a course of Alexander lessons was “staggeringly” effective and offered much more consistent long-term solutions than most of their other discussed options.

You can check out the article here!

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Concept Spotlight: Spirals

In the last Concept Spotlight, we discussed two of the “building blocks” of movement: primary and secondary curves. By way of a brief recap: primary is the fetal curve, the forward curling of the spine that mimics a baby in the womb. It’s called “primary” because it’s the first movement we do, taking place even before we are born. Secondary is the curve of spinal extension, what we might call “arching” the back. It begins when the baby’s neck muscles develop enough to support its head, allowing it to look up and placing a secondary curve in the cervical spine.

Put these two curves together at the same time and you get the third building block of movement: the spiral. When you break it down, a spiral can be described as a primary curve across one diagonal of the torso and a secondary curve across the other, taking place simultaneously. One shoulder tends forward towards primary while the other tends back towards secondary.

The spiral is a complex movement that can, fortunately, be executed effortlessly and quite naturally with the proper intention. Think back to Dart’s work and the idea of developmental movement. The most easily-noticeable first place to recognize a spiral is in a baby learning to roll over. If you’ve ever seen a baby rolling over for the first time, you’ll notice that the intention in her movement begins with the eyes. Perhaps the baby is lying on her stomach and getting a bit miffed that she can’t see her surroundings very well. She looks up and around to one side, allowing her torso to follow naturally as her hips stay weighted towards the floor, until finally the weight of the head overtakes the pelvis and she clunks gently over onto her back. The movement of the eyes is crucial to the effortless performance of this roll – the movement is what we often refer to as “head leads, body follows.”

And it’s not just restricted to humans, either – check out this video of a sea otter spinning through the water!

This spiraling pattern is integral to most of the movements we do everyday. As an Alexander teacher, I spend a lot of my time pointing out spirals within movements to students interested in performing them with more ease. Perhaps a ballet dancer is having trouble with an arabesque, and needs to pay more attention to the spiral through the supporting side of her body to maintain her balance. This photo shows one of my colleagues, Luc Vanier, leading a dancer through an arabesque-spiral exercise to increase her awareness of this connection.  Non-performers use spirals just as much, though – perhaps your dentist is chronically twisted to one side from years of standing on the same side of the chair to perform exams. Becoming aware of the spirals within your life is a simple way to begin to think spatially about the way you move – where are the spirals and are they balanced?

Non-performers use spirals just as much, though – perhaps your dentist is chronically twisted to one side from years of standing on the same side of the chair to perform exams. Becoming aware of the spirals within your life is a simple way to begin to think spatially about the way you move – where are the spirals and are they balanced?

Incidentally, most of us have one side that is an easier spiral than the other. Some research suggests that this side-favoring may go all the way back to our birth – when a baby is born, it spirals out of the birth canal, going from face-down to face-up as the body follows the head out of the mother. Perhaps your easier spiral is the way you turned when you were born!

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Book Review: Body Learning

For this month’s book review I dove into a book I’ve been wanting to read for years now. Body Learning, by Michael Gelb, was used multiple times during my own training, both as a student and as a teacher trainee. My teachers would wave it around and talk about what a good read it was, and I somehow just never managed to actually sit down with a copy. Now that I have, I see why they were so enthusiastic. Body Learning is a remarkably strong narrative about the Technique and what it’s like to live your life by it.

Gelb introduces Body Learning as the book he would have wanted when he started learning the Technique. He describes it as “inspiration and guidance for those who consider commencing this journey, and as refreshment for those who have been traveling it for a while.” (Preface to the second edition, vii) A fluid narrative and intuitive organization, coupled with great articulation and description of the principles, make this an easy read that really communicates the essence of the Technique. The book is targeted towards new students and experienced teachers alike, and everyone in between, making it a rare case where I find myself completely okay with recommending it to everyone.

The book begins, as so many others, with an overview of the principles and application of the Alexander Technique. Gelb makes liberal use of practical examples and discussion of applications from his own experiences and those of his students. Once the theory and practice are out of the way, the section “Further Adventures” discusses a few more recent experiences Gelb has had since the first publication of the book and how his own understanding is still growing and developing. Finally, the book ends with several unusual applications of the technique, connecting Alexander’s theories to subjects such as implementing change on an organizational level, understanding one’s own emotions, and cultivating successful interpersonal relationships.

The plethora of personal anecdotes breathes life into the material, making sure that it doesn’t devolve into dry philosophy but stays constantly connected to the practical everyday use of the work. After the obligatory discussion of Alexander’s discovery, Gelb transitions into his discussion of the principles by introducing seven “operational ideas” that guide the teaching of the Technique. These “operational ideas” are:

Use and Functioning

The Whole Person

Primary Control

Unreliable Sensory Appreciation

Inhibition

Direction

Ends and Means

and they are laid out just like that at the beginning of part 2. I appreciated this use of what my writing teacher used to call “signposting” – stating at the outset what you are going to talk about – because it helped to keep the section focused and give the reader a sense of where the discussion was going. Similarly, each “operational idea” section ends with a series of “checkpoints” – basically discussion questions to deepen the reader’s understanding of the material. Questions like “What does wholeness mean to you?” (p. 41) encourage the reader to put the book down for a moment and really think about what they’re reading, which helps to clear away the philosophy fuzz that sometimes grows in the brain when reading about the work for a prolonged period of time.

This is the part of the review where I’m supposed to talk about the weaknesses of the book, but to be honest, I couldn’t find many. If I have to nitpick, I’d say that the “Ends and Means” section has a surprising number of long blockquotes from other sources, far more quoted material than original material. While these blockquotes are well-chosen and do serve to articulate the points Gelb is making, when I see this many of them concentrated in a small space I become concerned that it might be an indicator of Gelb having trouble articulating the concepts in his own words. But, since the book reinforces time and again that Gelb’s own understanding of the work is still deepening and changing, I’d be inclined to forgive him for this. End-gaining and Means-whereby are some of the hardest concepts to articulate, and I’m sure his own understanding of how to articulate them is still growing.

Overall, Body Learning is a fantastic introduction to the Technique. I would highly recommend this book to anyone interested either in learning about the technique for the first time, or deepening their understanding further. While I have read other books that discuss the principles in perhaps easier-to-understand language, Gelb’s liberal use of anecdotes and practical examples allows for the same level of understanding despite the trickier language. I would definitely read this book in a group setting as well, since the Checkpoints are clearly designed to be discussed with a group. Body Learning has easily made it onto my short list of good books for interested students, new or old.

The Nitty-Gritty

Title: Body Learning

Author: Michael J. Gelb

© 1994 by Michael J. Gelb, published by Holt Paperbacks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC

ISBN-10: 0-8050-4206-7

ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-4206-1

Status: Available on Amazon

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Quote of the Month: January 2015

“Self-pity needs to give way to self-accusation.”

~Attributed to Alexander by Walter Carrington in the Foreword to Body Learning by Michael Gelb

It’s a new year, and for many that means time for resolutions, for enthusiastic statements about grand sweeping changes to be made to their lifestyle. I’ve recently started reading Body Learning by Michael Gelb, a book I’ve been wanting to read for years. In the Foreword by Walter Carrington, I found this little nugget of wisdom attributed to Alexander.

This is one of those quotes that can easily be misconstrued, because like many of Alexander’s statements the language can seem harsher than was probably intended. In this case, the idea of “self-accusation” can seem harsh, but I believe that rather than blaming oneself for everything that goes wrong, Alexander is simply saying that at some point, we need to take control of our decisions and acknowledge that we do have the power to change things we don’t like about our life.

This quote immediately reminded me of a decision I made last summer – removing “hopefully” from my vocabulary. I had begun to notice that when journalling about my thoughts, or talking to others about how my businesses were going, I had a tendency to use the word “hopefully” a lot. “Hopefully I’ll get more students,” “Hopefully such-and-such will happen,” “Hopefully I’ll be able to do this-that-or-the-other.” I didn’t like how powerless it made me feel, how inactive it sounded. I’ve never liked the idea of just “hoping” for something to happen, and the nature of the Technique in particular made it seem like direct marketing wasn’t very effective in actually gaining me more students. A student has to want to come for lessons, so all the marketing in the world isn’t really going to convince anyone who doesn’t already see the need for it. You can do your marketing, and then you just sort of hope that it works. I didn’t like that.

When you get right down to it, that sort of marketing is basically just end-gaining. What I needed was a means-whereby. I needed to stop hoping something would happen, and start making choices and taking actions that might eventually cause it to happen on its own. In the case of the “getting more students” problem, I decided to double-down on something I’d been slacking off on for a while: these blog posts! I figured that doing regular posts would be a way for me to stay involved, keep learning and expanding my own experience with the Technique, and give potential students a sense of my personality and how I work and think about the Technique. It would also keep me near the top of any online search results, since new content would be added regularly to the site. Further, the end-of-the-month book reviews were a way of tying in my Continuing Education hours. The decision to write regularly came from a place of self-accusation – there’s no point in just hoping for something when there IS something I can do, it’s just an indirect approach – which happens to be much more in tune with the Technique in the first place!

So this year, as you make your resolutions, think about this; my non-rhetorical question of the day: where are you self-pitying where you could be self-accusing?

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

A news article has been making the rounds of Alexander Teachers on the internet and I felt I should share it with you. The article discusses a new study, “Assessment of Stresses in the Cervical Spine Caused by Posture and Position of the Head,” that looks at the pressures put on the spine by the head when it’s in the most common “texting position.” Smart phones are new enough that this is one of the first studies to look in-depth at the effect of this new interface on our use and coordination. And it’s made mention of the Alexander Technique!

Near the end of the article, the leading surgeon of the study suggests that “The Alexander technique is worth exploring…as it’s a form of training that makes you aware of optimal body positioning.” This is great exposure for the Technique, especially since knowledge of AT usually spreads via word of mouth and as such is slow to reach new markets. Perhaps with the prevalence of texting and smartphones, more people will reach out to the Alexander Technique to help them figure out how to text without pain.

You can check out the article here. And if you’re having texting-related neck pain, consider contacting me for a demo lesson!

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Everyday Poise: Dare to be Wrong

I came across this Ted Talk the other day, and part of it struck me as a great articulation of an Alexander principle. Watch at least the first seven minutes of the video first, and then we’ll discuss.

At four minutes in he begins telling a story about his four-year-old son and the kids in his nativity play, and right around the 5 minute and 22 second mark, he says that “kids will take a chance. If they don’t know, they’ll have a go…they’re not frightened of being wrong.” He goes on to give a particularly exact articulation of an Alexander concept. He talks about the idea that if you are not prepared to be wrong, you can never come up with anything original. This is almost exactly the way that Alexander explains the idea of Faulty Sensory Appreciation.

According to Alexander, we can only consistently do our habits, the things that are known to us already. If something is unknown, we can’t rely on our senses to help us complete it, because we will try to be right and just go straight back into our habit again. The habit is what feels “correct,” so it’s what we will end up doing if we have the desire to do something right. In order to move from the known to the unknown, we have to be okay with being wrong. Ken’s argument here is that children don’t mind being wrong, and will take a chance at something they don’t already know, but as we age we lose that confidence and begin to be terrified of making mistakes. He discusses this in the context of creativity, and the idea that in order to be creative you have to be willing to live in the unknown and prepared to make mistakes. But it is just as applicable in the context of Alexander lessons, the idea being that in order to make changes in the way you use yourself and interact with your surroundings, you have to be willing to be “wrong” for a while.

The whole talk is intriguing and well worth the twenty minutes to watch it, and I highly recommend that you do.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Quote of the Month: August 2014

“I was on my way to Dictionopolis when I got stuck here,” explained Milo. “Can you help me?”

“Help you! You must help yourself,” the dog replied, carefully winding himself with his left hind leg. “I suppose you know why you got stuck.”

“I guess I just wasn’t thinking,” said Milo.

“PRECISELY,” shouted the dog as his alarm went off again. “Now you know what you must do.”

“I’m afraid I don’t,” admitted Milo, feeling quite stupid.

“Well,” continued the watchdog impatiently, “since you got here by not thinking, it seems reasonable to expect that, in order to get out, you must start thinking.”

…

and as they raced along the road MIlo continued to think of all sorts of things; of the many detours and wrong turns that were so easy to take, of how fine it was to be moving along, and, most of all, of how much could be accomplished with just a little thought.

~The Phantom Tollbooth, by Norton Juster

The Phantom Tollbooth has been one of my favorite children’s books ever since the first time I read it. Re-reading it again, I was struck by this passage and how similar it is to the philosophy of the Alexander Technique. The watchdog’s comment about starting to think sounds almost like something one of my teachers would have said.

The idea that amazing things can be accomplished with just a little thought is central to the Alexander Technique. When we stop thinking as Milo does, we are liable to end up taking all sorts of detours in the way we use ourselves. As these detours pile up we invariably end up stuck in our bad habits, and it becomes nearly impossible to get out. The way out is exactly what the watchdog says – if you got into a pattern of use by not thinking, then to get out you must start thinking. Alexander referred to this as Constructive Conscious Control – the idea being that you must learn to consciously affect your own use and convert subconscious habits into conscious choices.

The watchdog is also right, by the way, in saying that he can’t help Milo – Milo must help himself. Your Alexander teacher is there to help you figure out how to help yourself, just as the watchdog helps Milo figure out what he needs to do. But in the end, the changes will only happen consistently if you want them to happen and you allow them to happen.

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.

Principles of the Alexander Technique, by Jeremy Chance, is a slim volume in the Singing Dragon’s “Principles Of” series, much like Secrets of Alexander Technique was a volume in the “Secrets of” series. Other books in the series deal with topics such as herbal medicine, reflexology, Reiki and hypnotherapy. Principles of AT serves as a basic overview of AT, with a particular focus on the experience of having lessons. Overall it’s a decent showing, with clear, concise language and well-turned phrases, though the heavy focus on what the work “feels like” does raise a few red flags for me. The book seems to be targeted towards the average person seeking help, with a particular emphasis on helping those who cannot find a teacher nearby.

The book begins with a narrative description of Alexander’s process of development, introducing each major principle at the moment in Alexander’s journey when he discovered it in himself. In this way Chance manages to cover both the history and development of the technique and the major principles behind it all at once, creating a narrative that is concise and understandable. From there the book spends quite a bit of time discussing the practical side of the technique – what happens in a lesson, the differences between teachers and teaching styles, and how to find a teacher whose personality meshes with yours. The last chapter discusses various experiments and explorations that can be attempted alone, as a way of trying to get a little bit of the experience of a lesson without a teacher. The book communicates its information through clear explanations augmented with photographs, diagrams, and quotes from Alexander himself. The quotes in particular are used very skillfully, generally introducing a quote as a way of summing up a concept that the author has just finished explaining in his own words. Emphasis is placed on using the snappier quotes – the ones that Alexander teachers frequently quote in lessons, such as “the right thing does itself” – rather than longer or more involved descriptive language from Alexander’s books.

Chance’s writing ability shines as the book’s major strength, with concepts articulated very concisely with a clear and frank tone. He makes use of helpful analogies and examples to compare the principles to understandable situations, such as New Year’s resolutions or doing the dishes. This allows him to skillfully cover the basic principles behind the work without it sounding too new-age-y or ivory-tower philosophical. Chance also incorporates a welcome discussion of various practical aspects of studying the technique, such as teacher lineages and the differences between them, the distinctions between ATI and STAT/AmSAT certification programs, and examples of the different ways different teachers might approach the material. This leaves the reader with a more concrete sense of what they’d actually be doing in a lesson – a question that most introductory discussions of the technique never really answer. (To be fair, though, most introductions never answer that question because the most appropriate answer is ‘you won’t be doing anything’ followed by a lengthy explanation of the principles of inhibition).

Despite the skillful writing, Principles of AT has some worrisome weaknesses at its core. Chapter 6: “Working with your Self Alone” worries me quite a lot; it places a great deal of emphasis on feeling, without enough mention of the concept of Faulty Sensory Appreciation and the idea that what you feel is happening isn’t necessarily what is actually happening. Without a teacher present it becomes even more important to observe in a mirror and not trust your own feeling, and yet the entire chapter is full of experiments designed to rely on feeling. To make matters worse, the book also frequently offers suggestions of what experience the reader may be having (“By now it will become clearer that you are twisting your body a little to the left or the right” – P. 141). These suggestions are things that the author has no way of actually knowing about the reader, and the simple act of mentioning it is placing thoughts into the reader’s head – something we try to avoid in an actual lesson! I appreciate that the author is attempting to offer up some way of working with the principles to interested readers who cannot find a teacher in their area, but when working alone it is imperative that the student remembers not to trust their sensory appreciation. Principles of AT needs to place much more importance on this fact.

Principles of AT also has some typographical problems. There are a disconcerting number of typos (in my edition, at least), and they are all mistakes that indicate that the manuscript was not proofread by a pair of human eyes. All of these typos are things that a computerized spell-checker would have missed, since they are typos that convert one word into another word (i.e. “rib” is misprinted as “rig”). While not a horrendous mistake, they do make the book more difficult to read and seem a bit unprofessional.

Principles of AT does have some strong points – the principles are explained well and the writing is good – but for me the over-emphasis on feeling and lack of discussion of unreliable sensory appreciation in the last few chapters are a deal-breaker. I could see myself loaning this book to a student for them to read some specific part – perhaps something from the earlier chapters containing a well-written explanation of a principle they were confused about – but I would not be comfortable simply handing it over in its entirety as a first introduction; there is just too much potential for misinterpretation. The discussion of the principles is well-articulated and pragmatic, and the discussion of teacher lineages and certification systems is welcome and thorough, but I would want anyone reading it to stop at the beginning of chapter 6, “Working with your Self Alone,” and read no further lest they be confused and misled by the experiments within. I suppose the experiments could be interesting for a student who was currently taking lessons, if they tried them under the careful supervision of their teacher, but there are better books for that. Rather than these experiments, I would recommend the ones contained in The Alexander Technique by Judith Leibowitz and Bill Connington or Dance and the Alexander Technique: Exploring the Missing Link by Becky Nettl-Fiol and Luc Vanier.

The Nitty-Gritty

Title: Principles of the Alexander Technique

Author: Jeremy Chance

© 2013 by Singing Dragon, an imprint of Jessica Kingsley Publishers

ISBN-10: 1848191286

ISBN-13: 978-1848191280

Status: Available on Amazon

Forward and Up! is a Pittsburgh-based private practice offering quality instruction in the Alexander Technique in a positive and supportive environment.